Almost a year has passed since the HoneyComb development kit was released by SolidRun. I remember reading about this Mini-ITX Arm workstation board being released and thinking “what a great idea.” Then I saw the price and realized this isn’t just another Raspberry Pi killer. Currently that price is $750 USD plus shipping and duty. Niche devices like the HoneyComb aren’t mass produced like the simpler Pi is, and they pack in quite a bit of high end tech. Eventually COVID lockdown boredom got the best of me and I put a build together. Adding a case and RAM, the build ended up costing about $1100 shipped to London. This is a recount of my experiences and the current state of using Fedora on this fun bit of hardware.

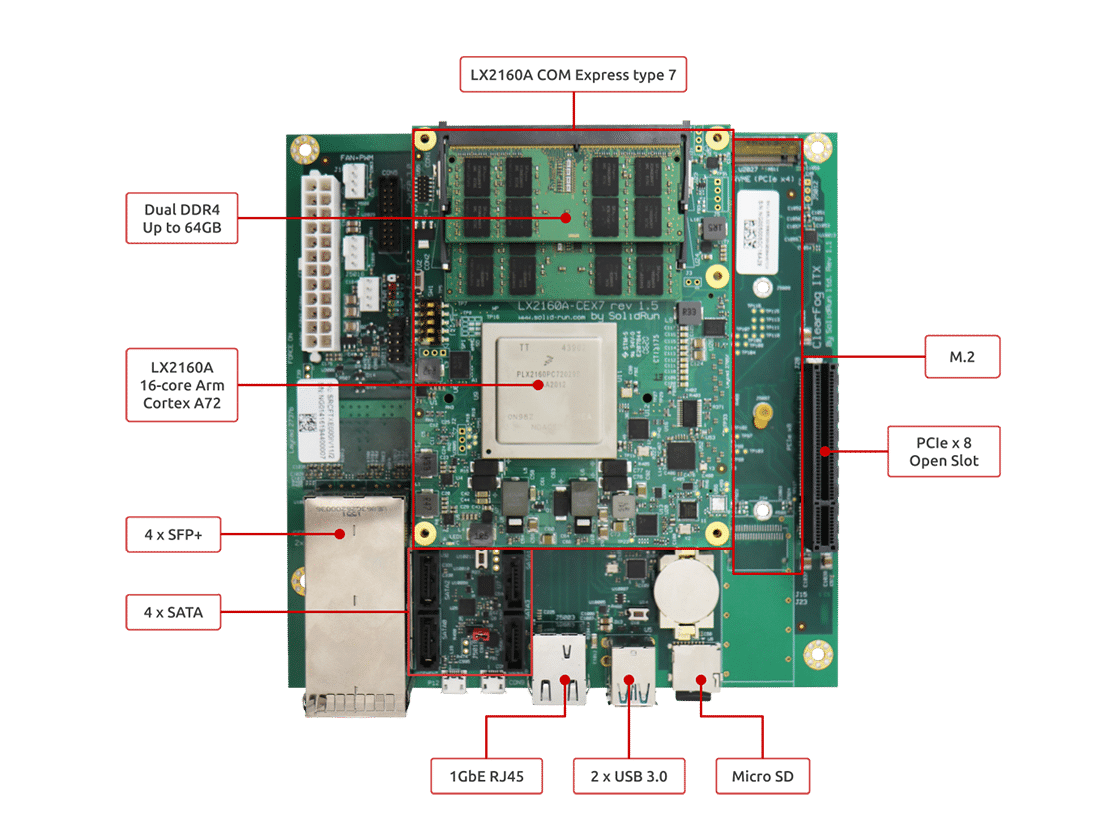

First and foremost, the tech packed into this board is impressive. It’s not about to kill a Xeon workstation in raw performance but it’s going to wallop it in performance/watt efficiency. Essentially this is a powerful server in the energy footprint of a small laptop. It’s also a powerful hybrid of compute and network functionality, combining powerful network features in a carrier board with modular daughter card sporting a 16-core A72 with 2 ECC-capable DDR4 SO-DIMM slots. The carrier board comes in a few editions, giving flexibility to swap or upgrade your RAM + CPU options. I purchased the edition pictured below with 16 cores, 32GB (non-ECC), 512GB NVMe, and 4x10Gbe. For an extra $250 you can add the 100Gbe option if you’re building a 5G deployment or an ISP for a small country (bottom right of board). Imagine this jacked into a 100Gb uplink port acting as proxy, tls inspector, router, or storage for a large 10gb TOR switch.

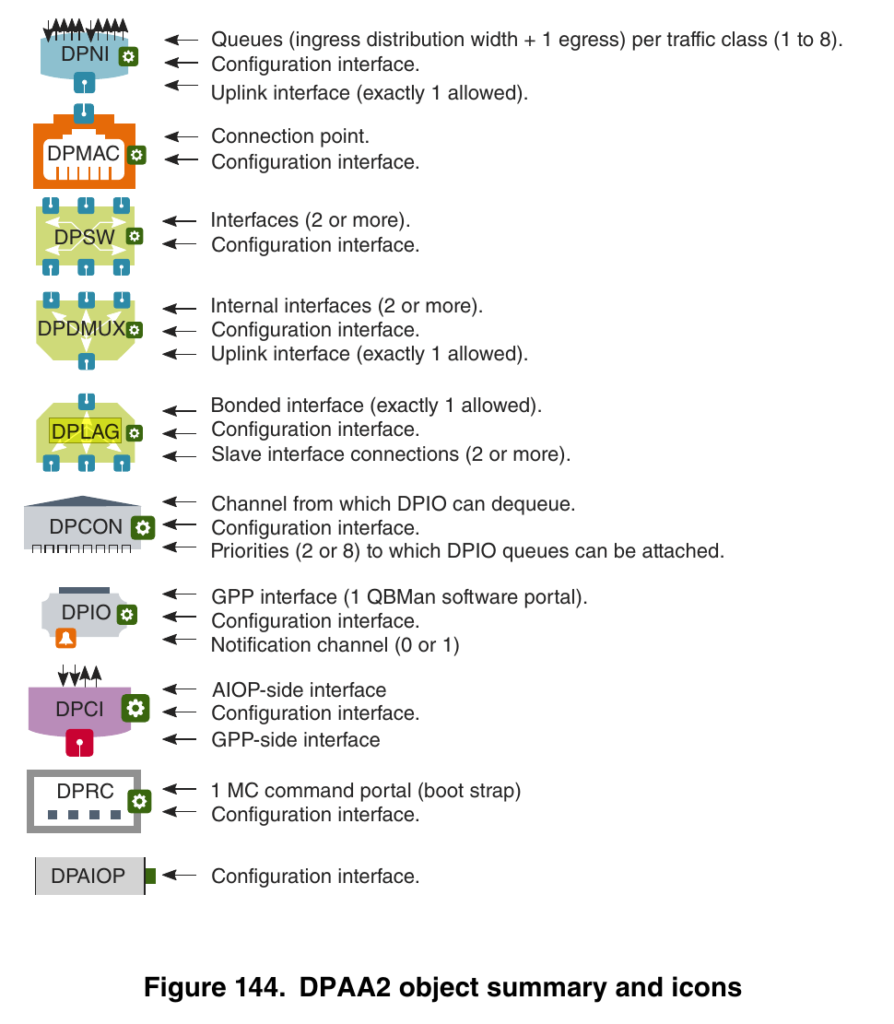

When I ordered it I didn’t fully understand the network co processor included from NXP. NXP is the company that makes the unique LX2160A CPU/SOC for this as well as configurable ports and offload engine that enable handling up to 150Gb/s of network traffic without the CPU breaking a sweat. Here is a list of options from NXP’s Layerscape user manual.

I have a 10gb network in my home attic via a Ubiquiti ES-16-XG so I was eager to see how much this board could push. I also have a QNAP connected via 10gb which rarely manages to saturate the line, so could this also be a NAS replacement? It turned out I needed to sort out drivers and get a stable install first. Since the board has been out for a year, I had some catching up to do. SolidRun keeps an active Discord on Developer-Ecosystem which was immensely helpful as install wasn’t as straightforward as previous blogs have mentioned. I’ve always been cursed. If you’ve ever seen Pure Luck, I’m bound to hit every hardware glitch.

For starters, you can add a GPU and install graphically or install via USB console. I started with a spare GPU (Radeon Pro WX2100) intending to build a headless box which in the end over-complicated things. If you need to swap parts or re-flash a BIOS via the microSD card, you’ll need to swap display, keyboard + mouse. Chaos. Much simpler just to plug into the micro USB console port and access it via /dev/ttyUSB0 for that picture-in-picture experience. It’s really great to have the open ended PCIe3-x8 slot but I’ll keep it open for now. Note that the board does not support PCIe Atomics so some devices may have compatibility issues.

Now comes the fun part. BIOS is not built-in here. You’ll need to build from source for to your RAM speed and install via microSDHC. At first this seems annoying but then you realize that with removable BIOS installer it’s pretty hard to brick this thing. Not bad. The good news is the latest UEFI builds have worked well for me. Just remember that every time you re-flash your BIOS you’ll need to set everything up again. This was enough to boot Fedora aarch64 from USB. The board offers 64GB of eMMC flash which you can install to if you like. I immediately benched it to find it reads about 165MB/s and writes 55MB/s which is practical speed for embedded usage but I’ll definitely be installing to NVMe instead. I had an older Samsung 950 Pro in my spares from a previous Linux box but I encountered major issues with it even with the widely documented kernel param workaround:

nvme_core.default_ps_max_latency_us=0

In the end I upgraded my main workstation so I could repurpose its existing Samsung EVO 960 for the HoneyComb which worked much better.

After some fidgeting I was able to install Fedora but it became apparent that the integrated network ports still don’t work with the mainline kernel. The NXP tech is great but requires a custom kernel build and tooling. Some earlier blogs got around this with a USB->RJ45 Ethernet adapter which works fine. Hopefully network support will be mainlined soon, but for now I snagged a kernel SRPM from the helpful engineers on Discord. With the custom kernel the 1Gbe NIC worked fine, but it turns out the SFP+ ports need more configuration. They won’t be recognized as interfaces until you use NXP’s restool utility to map ports to their usage. In this case just a runtime mapping of dmap -> dni was required. This is NXP’s way of mapping a MAC to a network interface via IOCTL commands. The restool binary isn’t provided either and must be built from source. It then layers on management scripts which use cheeky $arg0 references for redirection to call the restool binary with complex arguments.

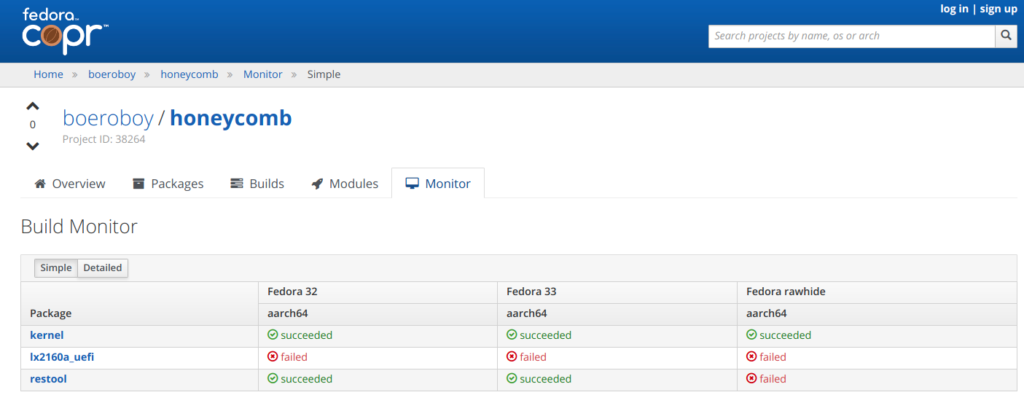

Since I was starting to accumulate quite a few custom packages it was apparent that a COPR repo was needed to simplify this for Fedora. If you’re not familiar with COPR I think it’s one of Fedora’s finest resources. This repo contains the uefi build (currently failing build), 5.10.5 kernel built with network support, and the restool binary with supporting scripts. I also added a oneshot systemd unit to enable the SFP+ ports on boot:

systemd enable --now dpmac@7.service

systemd enable --now dpmac@8.service

systemd enable --now dpmac@9.service

systemd enable --now dpmac@10.service

Now each SPF+ port will boot configured as eth1-4, with eth0 being the 1Gb. NetworkManager will struggle unless these are consistent, and if you change the service start order the eth devices will re-order. I actually put a sleep $@ in each activation so they are consistent and don’t have locking issues. Unfortunately it adds 10 seconds to boot time. This has been fixed in the latest kernel and won’t be an issue once mainlined.

I’d love to explore the built-in LAG features but this still needs to be coded into the

options. I’ll save it for later. In the meantime I managed a single 10gb link as primary, and a 3×10 LACP Team for kicks. Eventually I changed to 4×10 LACP via copper SFP+ cables mounted in the attic.

Energy Efficiency

Now with a stable environment it’s time to raise some hell. It’s really nice to see PWM support was recently added for the CPU fan, which sounds like a mini jet engine without it. Now the sound level is perfectly manageable and thermal control is automatic. Time to test drive with a power meter. Total power usage is consistently between 20-40 watts (usually in the low 20s) which is really impressive. I tried a few tuned profiles which didn’t seem to have much effect on energy. If you add a power-hungry GPU or device that can obviously increase but for a dev server it’s perfect and well below the Z600 workstations I have next to it which consume 160-250 watts each when fired up.

Remote Access

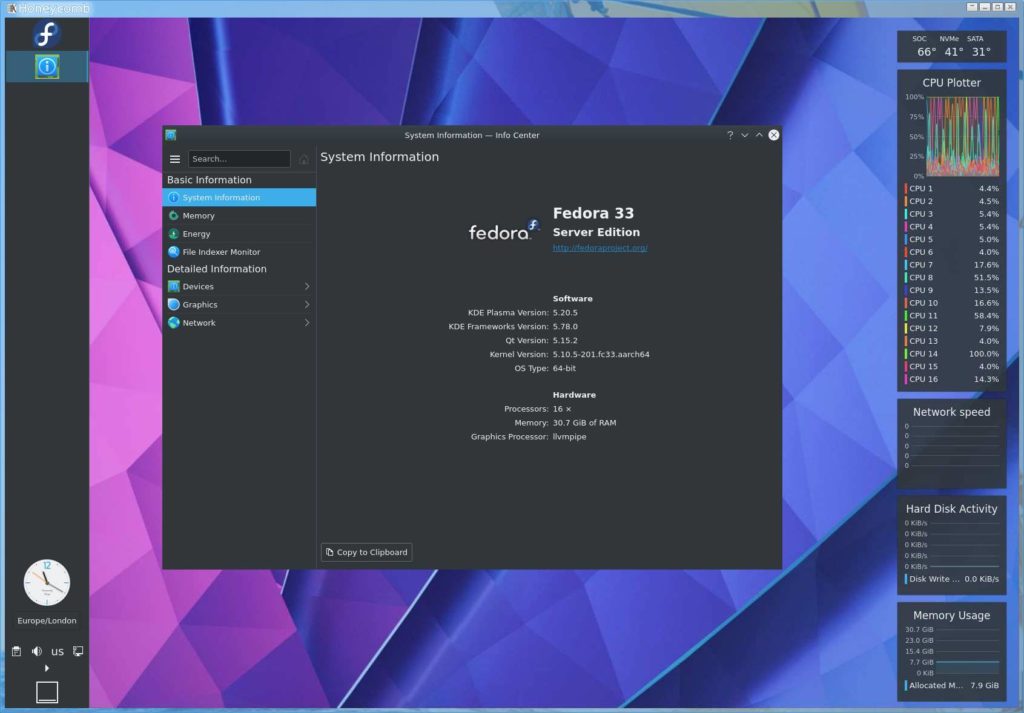

I’m an old soul so I still prefer KDE with Xorg and NX via X2go server. I can access SSH or a full GUI at native performance without a GPU. This lets me get a feel for performance, thermal stats, and also helps to evaluate the device as a workstation or potential VDI. The version of KDE shipped with the aarch64 server spin doesn’t seem to recognize some sensors but that seems to be because of KDE’s latest widget changes which I’d have to dig into.

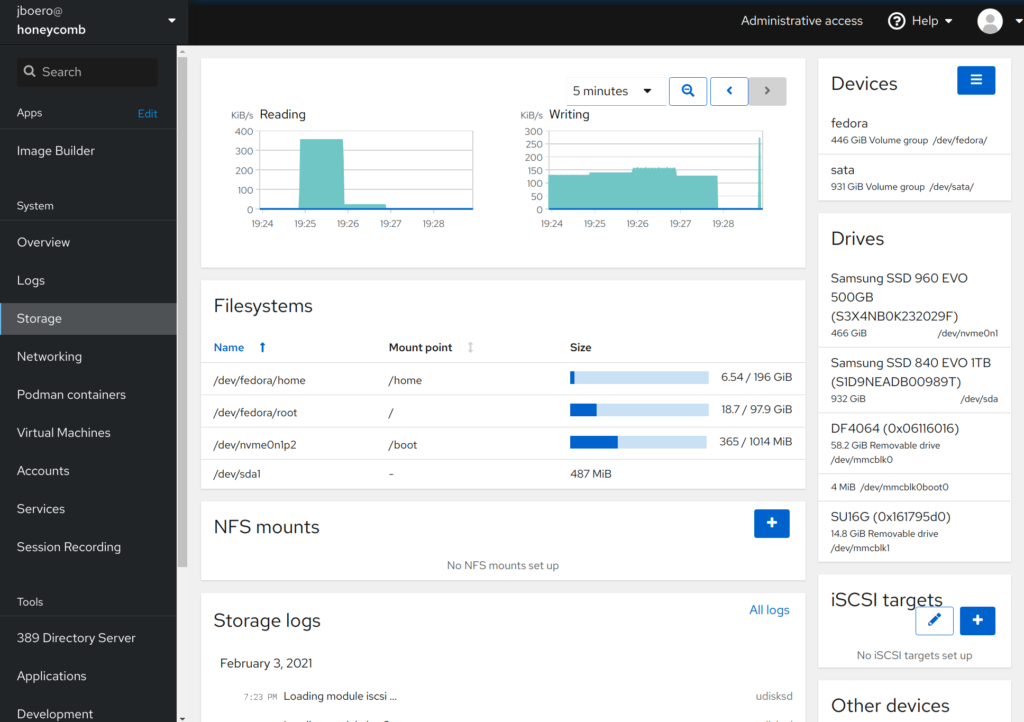

Cockpit support is also outstanding out of the box. If SSH and X2go remote access aren’t your thing, Cockpit provides a great remote management platform with a growing list of plugins. Everything works great in my experience.

All I needed to do now is shift into high gear with jumbo frames. MTU 1500 yields me an iperf of about 2-4Gbps bottlenecked at CPU0. Ain’t nobody got time for that. Set MTU 9000 and suddenly it gets the full 10Gbps both ways with time to spare on the CPU. Again, it would be nice to use the hardware assisted LAG since the device is supposed to handle up to 150Gbps duplex no sweat (with the 100Gbe QSFP option), which is nice given the Ubiquiti ES-16-XG tops out at 160Gbps full duplex (10gb/16 ports).

Storage

As a storage solution this hardware provides great value in a small thermal window and energy saving footprint. I could accomplish similar performance with an old x86 box for cheap but the energy usage alone would eclipse any savings in short order. By comparison I’ve seen some consumer NAS devices offer 10Gbe and NVMe cache sharing an inadequate number of PCIe2 lanes and bottlenecked at the bus. This is fully customizable and since the energy footprint is similar to a small laptop a small UPS backup should allow full writeback cache mode for maximum performance. This would make a great oVirt NFS or iSCSI storage pool if needed. I would pair it with a nice NAS case or rack mount case with bays. Some vendors such as Bamboo are actually building server options around this platform as we speak.

The board has 4 SATA3 ports but if I were truly going to build a NAS with this I would probably add a RAID card that makes best use of the PCIe8x slot, which thankfully is open ended. Why some hardware vendors choose to include close-ended PCIe 8x,4x slots is beyond me. Future models will ship with a physical x16 slot but only 8x electrically. Some users on the SolidRun Discord talk about bifurcation and splitting out the 8 PCIe lanes which is an option as well. Note that some of those lanes are also reserved for NVMe, SATA, and network. The CEX7 form factor and interchangeable carrier board presents interesting possibilities later as the NXP LX2160A docs claim to support up to 24 lanes. For a dev board it’s perfectly fine as-is.

Network Perf

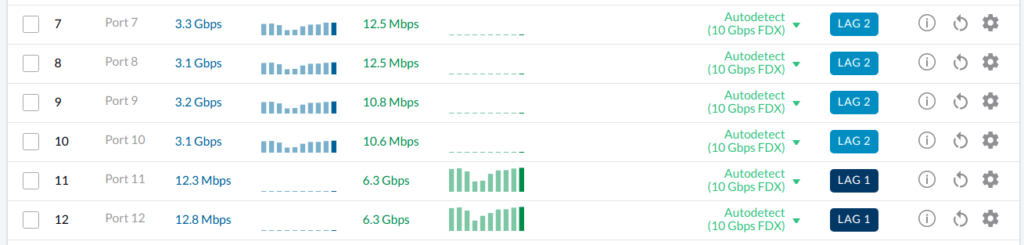

For now I’ve managed to rig up a 4×10 LACP Team with NetworkManager for full load balancing. This same setup can be done with a QSFP+ breakout cable. KDE nm Network widget still doesn’t support Teams but I can set them up via nm-connection-editor or Cockpit. Automation could be achieved with nmcli and teamdctl. An iperf3 test shows the connection maxing out at about 13Gbps to/from the 2×10 LACP team on my workstation. I know that iperf isn’t a true indication of real-world usage but it’s fun for benchmarks and tuning nonetheless. This did in fact require a lot of tuning and at this point I feel like I could fill a book just with iperf stats.

$ iperf3 -c honeycomb -P 4 --cport 5000 -R Connecting to host honeycomb, port 5201 Reverse mode, remote host honeycomb is sending [ 5] local 192.168.2.10 port 5000 connected to 192.168.2.4 port 5201 [ 7] local 192.168.2.10 port 5001 connected to 192.168.2.4 port 5201 [ 9] local 192.168.2.10 port 5002 connected to 192.168.2.4 port 5201 [ 11] local 192.168.2.10 port 5003 connected to 192.168.2.4 port 5201 [ ID] Interval Transfer Bitrate [ 5] 1.00-2.00 sec 383 MBytes 3.21 Gbits/sec [ 7] 1.00-2.00 sec 382 MBytes 3.21 Gbits/sec [ 9] 1.00-2.00 sec 383 MBytes 3.21 Gbits/sec [ 11] 1.00-2.00 sec 383 MBytes 3.21 Gbits/sec [SUM] 1.00-2.00 sec 1.49 GBytes 12.8 Gbits/sec - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - (TRUNCATED) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - [ 5] 2.00-3.00 sec 380 MBytes 3.18 Gbits/sec [ 7] 2.00-3.00 sec 380 MBytes 3.19 Gbits/sec [ 9] 2.00-3.00 sec 380 MBytes 3.18 Gbits/sec [ 11] 2.00-3.00 sec 380 MBytes 3.19 Gbits/sec [SUM] 2.00-3.00 sec 1.48 GBytes 12.7 Gbits/sec - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - [ ID] Interval Transfer Bitrate Retr [ 5] 0.00-10.00 sec 3.67 GBytes 3.16 Gbits/sec 1 sender [ 5] 0.00-10.00 sec 3.67 GBytes 3.15 Gbits/sec receiver [ 7] 0.00-10.00 sec 3.68 GBytes 3.16 Gbits/sec 7 sender [ 7] 0.00-10.00 sec 3.67 GBytes 3.15 Gbits/sec receiver [ 9] 0.00-10.00 sec 3.68 GBytes 3.16 Gbits/sec 36 sender [ 9] 0.00-10.00 sec 3.68 GBytes 3.16 Gbits/sec receiver [ 11] 0.00-10.00 sec 3.69 GBytes 3.17 Gbits/sec 1 sender [ 11] 0.00-10.00 sec 3.68 GBytes 3.16 Gbits/sec receiver [SUM] 0.00-10.00 sec 14.7 GBytes 12.6 Gbits/sec 45 sender [SUM] 0.00-10.00 sec 14.7 GBytes 12.6 Gbits/sec receiver iperf Done

Notes on iperf3

I struggled with LACP Team configuration for hours, having done this before with an HP cluster on the same switch. I’d heard stories about bonds being old news with team support adding better load balancing to single TCP flows. This still seems bogus as you still can’t load balance a single flow with a team in my experience. Also LACP claims to be fully automated and easier to set up than traditional load balanced trunks but I find the opposite to be true. For all it claims to automate you still need to have hashing algorithms configured correctly at switches and host. With a few quirks along the way I once accidentally left a team in broadcast mode (not LACP) which registered duplicate packets on the iperf server and made it look like a single connection was getting double bandwidth. That mistake caused confusion as I tried to reproduce it with LACP.

Then I finally found the LACP hash settings in Ubiquiti’s new firmware GUI. It’s hidden behind a tiny pencil icon on each LAG. I managed to set my LAGs to hash on Src+Dest IP+port when they were defaulting to MAC/port. Still I was only seeing traffic on one slave of my 2×10 team even with parallel clients. Eventually I tried parallel clients with -V and it all made sense. By default iperf3 client ports are ephemeral but they follow an even sequence: 42174, 42176, 42178, 42180, etc… If your lb hash across a pair of sequential MACs includes src+dst port but those ports are always even, you’ll never hit the other interface with an odd MAC. How crazy is that for iperf to do? I tried looking at the source for iperf3 and I don’t even see how that could be happening. Instead if you specify a client port as well as parallel clients, they use a straight sequence: 50000, 50001, 50002, 50003, etc.. With odd+even numbers in client ports, I’m finally able to LB across all interfaces in all LAG groups. This setup would scale out well with more clients on the network.

Everything could probably be tuned a bit better but for now it is excellent performance and it puts my QNAP to shame. I’ll continue experimenting with the network co-processor and seeing if I can enable the native LAG support for even better performance. Across the network I would expect a practical peak of about 40 Gbps raw which is great.

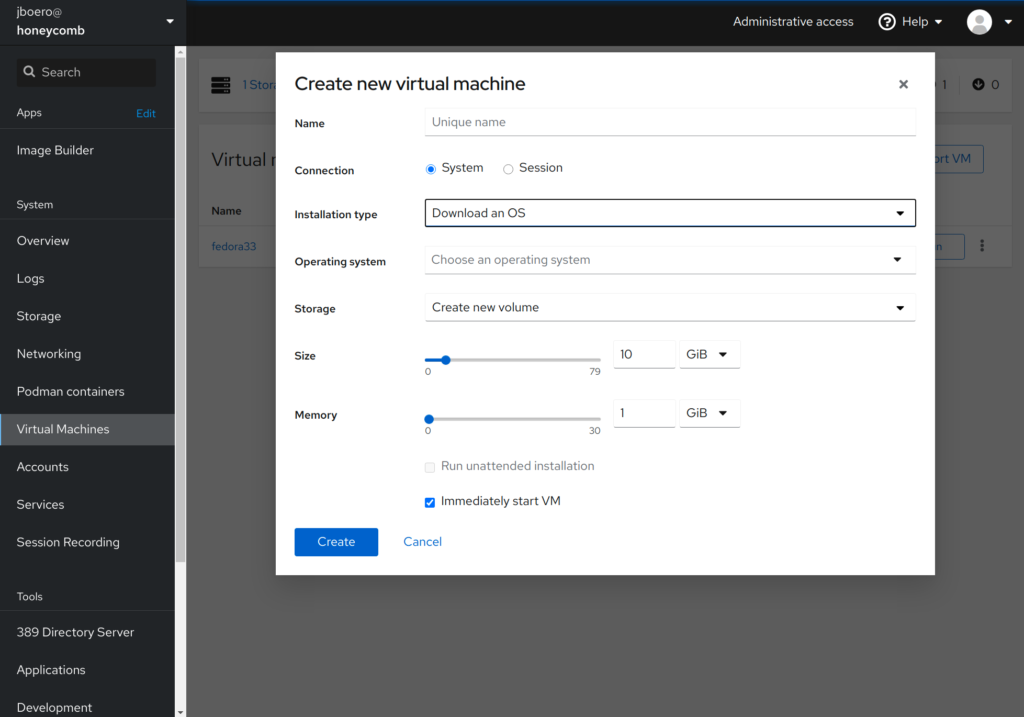

Virtualization

What about virt? One of the best parts about having a 16 A72 cores is support for Aarch64 VMs at full speed using KVM, which you won’t be able to do on x86. I can use this single box to spin up a dozen or so VMs at a time for CI automation and testing, or just to test our latest HashiCorp builds with aarch64 builds on COPR. Qemu on x86 without KVM can emulate aarch64 but crawls by comparison. I’ve not yet tried to add it to an oVirt cluster yet but it’s really snappy actually and proves more cost effective than spinning up Arm VMs in a cloud. One of the use cases for this environment is NFV, and I think it fits it perfectly so long as you pair it with ECC RAM which I skipped as I’m not running anything critical. If anybody wants to test drive a VM DM me and I’ll try to get you some temp access.

Benchmarks

Phoronix has already done quite a few benchmarks on OpenBenchmarking.org but I wanted to rerun them with the latest versions on my own Fedora 33 build for consistency. I also wanted to compare them to my Xeons which is not really a fair comparison. Both use DDR4 with similar clock speeds – around 2Ghz but different architectures and caches obviously yield different results. Also the Xeons are dual socket which is a huge cooling advantage for single threaded workloads. You can watch one process bounce between the coolest CPU sockets. The Honeycomb doesn’t have this luxury and has a smaller fan but the clock speed is playing it safe and slow at 2Ghz so I would bet the SoC has room to run faster if cooling were adjusted. I also haven’t played with the PWM settings to adjust the fan speed up just in case. Benchmarks performed using the tuned profile network-throughput.

Strangely some single core operations seem to actually perform better on the Honeycomb than they do on my Xeons. I tried single-threaded zstd compression with default level 3 on a a few files and found it actually performs consistently better on the Honeycomb. However using the actual pts/compress-zstd benchmark with multithreaded option turns the tables. The 16 cores still manage an impressive 2073 MB/s:

Zstd Compression 1.4.5:

pts/compress-zstd-1.2.1 [Compression Level: 3]

Test 1 of 1

Estimated Trial Run Count: 3

Estimated Time To Completion: 9 Minutes [22:41 UTC]

Started Run 1 @ 22:33:02

Started Run 2 @ 22:33:53

Started Run 3 @ 22:34:37

Compression Level: 3:

2079.3

2067.5

2073.9

Average: 2073.57 MB/s

For apples to oranges comparison my 2×10 core Xeon E5-2660 v3 box does 2790 MB/s, so 2073 seems perfectly respectable as a potential workstation. Paired with a midrange GPU this device would also make a great video transcoder or media server. Some users have asked about mining but I wouldn’t use one of these for mining crypto currency. The lack of PCIe atomics means certain OpenCL and CUDA features might not be supported and with only 8 PCIe lanes exposed you’re fairly limited. That said it could potentially make a great mobile ML, VR, IoT, or vision development platform. The possibilities are pretty open as the whole package is very well balanced and flexible.

Conclusion

I wasn’t organized enough this year to arrange a FOSDEM visit but this is something I would have loved to talk about. I’m definitely glad I tried out. Special thanks to Jon Nettleton and the folks on SolidRun’s Discord for the help and troubleshooting. The kit is powerful and potentially replaces a lot of energy waste in my home lab. It provides a great Arm platform for development and it’s great to see how solid Fedora’s alternative architecture support is. I got my Linux start on Gentoo back in the day, but Fedora really has upped it’s arch game. I’m really glad I didn’t have to sit waiting for compilation on a proprietary platform. I look forward to the remaining patches to be mainlined into the Fedora kernel and I hope to see a few more generations use this package, especially as Apple goes all in on Arm. It will also be interesting to see what features emerge if Nvidia’s Arm acquisition goes through.